When your place of origin is no longer your belonging

In her graphic novel "Belonging", Nora Krug researches her family's role and what their actions during World War II meant for her own attachment to Germany: Her whole life is marked by guilt – she feels guilty for the Holocaust based on her nationality as a German. Her feelings of guilt are so extensive that she does not want to or cannot identify with her home country. In her new home – New York City in America – she meets her husband and marries into his Jewish family. Even then, she wonders if it can make her feel a little less guilty. Until she decides to check her guilt: In order to enlighten herself and to relieve herself of the feelings of guilt, she tries to trace the life of several family members and put the individual pieces of the puzzle together: Can she find out how deeply the ideologies of the Nazis were ingrained in the minds of her family? Or were they actually good people? She begins with a few clues that grow into a large amount of information during her two years of research: she finds documents, reads diaries, looks at old photos. She tries to link historical backgrounds with family stories. Some things remain unanswered – including whether the research has changed her understanding of her own identity.

What does home mean for someone who, due to historical events, has moved as far away from his origins as Nora Krug or my grandparents? They were evicted from Hungary in 1946 and I grew up with the identity that this part of my family is really from Hungary. Until, because of Nora Krug's journey, I wanted to know more about the circumstances and the history of my family – because history has to do with my identity today. Just as she writes in her book: "How do you know who you are, if you don't understand where you come from?"

My fellow student Luna Wolf explains in her article what "Belonging" or "Heimat" as we call it in German or "Moledet" in Isreal means, why the feeling of being home matters.

Nora Krug left her home Germany voluntarily, but my family did not. How important is it to me today that you came to Germany from Hungary immediately after the war? Why was there a German-speaking family in Hungary at all? And how were they involved during the Nazi era and the war? Was it even possible that in the villages where my ancestors lived, hardly anything could be heard of the extermination of the Jews?

Hungary before World War II: Why were the Germans – or Danube Swabians – in Hungary?

Before the Second World War began, Hungary was a multi-ethnic state. The cultural diversity and the mixed identities were consciously colonized in Hungary: After the Ottoman Wars were over, the places in Hungary were therefore depopulated and deserted. Which is why advertisers called for settling in southern Hungary on behalf of the Habsburgs in the 18th century. The different ethnic groups should lead the country to new economic strength with the knowledge which shaped them in their homeland. Settlers who emigrated to Hungary received financial and material support to build houses and farms. Skilled workers and craftsmen were wanted to rebuild, and the settlers should continue to defend the areas.

Immigration to Hungary was initially only allowed for people of the Catholic faith. Later, the regulation was less strict so that Protestant and Orthodox believers were also allowed to emigrate. Nevertheless, Jewish believers immigrated to Hungary in the 18th century. They were denied basic rights for a long time until the 19th century.

Some German Settlers – mostly the poorer sections of the population – emigrated to the places where my grandparents, great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents were born: Dunakömlőd and Beremend were both repopulated in the 18th century and at least one can say that Dunakömlőd was a German community. Dunakömlőd was also settled during the Josephine settlement action between 1784 and 1787. During that time 10,000 families with 45,000 people came to Hungary.

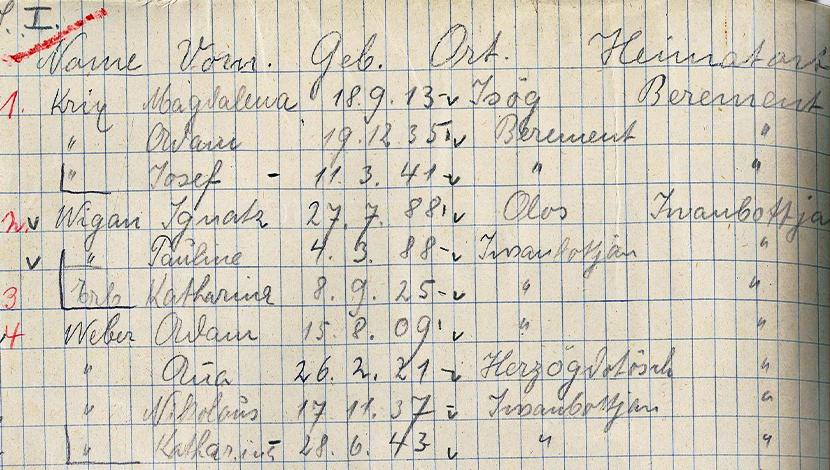

So my family on the side of my grandmother Maria were German settlers in Hungary – so-called Danube Swabians, who were expelled and expropriated after the Second World War. Also after being home there for at least 76 years. My grandfather Adam came from Beremend, but every single family member – including his parents – was born in a different place in Hungary. In summary, almost all of them come from places that are mostly close to each other in Baranya County. All the places of birth and residence – Beremend, Ivánbattyán, Villány, Kásád in Baranya and Gara and Vaskut in Bács-Kiskun – are along and near the border with Croatia and Serbia.

Hungary during World War II: Allied with National Socialist ideologies

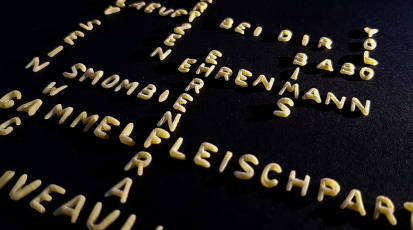

Often a majority of people of German origin lived in the villages. Even today, citizen censuses at the places of origin of my grandparents are differentiated into nationality affiliation. The distribution changed again and again due to further occupations. But what happened during World War II in the area where my family used to live? While an association was founded in Ivánbattyán (the place where my great-great-grandparents lived around 1940) in 1939 to cultivate Germanism, the population was happy to act it out. Above all, because Hitler's campaigns seemed successful to them and most of them felt connected to the German people, writes a contemporary witness. Until 1942 when the Waffen-SS ("Armed SS") advertised – at that time five people volunteered. The acceptance allegedly waned. "The youth, as well as the adults, split in two directions. So that the whole population was affected, and it broke in two directions." Those who did not volunteer and were under 50 years of age were forcibly recruited. He does not write who volunteered and who was critical. But my great-great-grandfather Ignaz was 54 years old at the time.

My great-grandfather Adam and his two sons Adam and Josef from Dunakömlőd were at war for the German armed forces. According to the family tree, those three family members fell in 1944. I found a death certificate from 1963 that says: He died on May 6, 1945, at 1.30 p.m. in Romnikus-Sarat / Romania in a prisoner-of-war camp. What happened to his sons remains unknown.

While Hungary was initially Nazi-Germany's ally, 1944 Hungary tried to leave the alliance and thwart the extermination of the Hungarian Jews. The Nazi forces did not accept that, occupied Hungary in 1944 and tried to complete the holocaust together with local antisemitic forces like the so called “Arrow Cross Party”. Around 437,000 Jews were deported from Hungary in July 1944. Also from southern Hungary, where my family comes from. Before the war, a total of 825,000 Jews lived in Hungary, 565,000 of them were killed in the Holocaust. Pécs is one of the few cities where Jewish communities still live today. It is located in Baranya County where my family lived.

The idea of the Habsburgs that all identities could benefit from one another was lost due to the Nazi regime of the Germans. Suddenly people were sorted out by ethnicity.

Hungary after World War II: Why Danube-Swabians were expelled

In 1946, around 250,000 of 700,000 Germans were expelled from Hungary. One of our cousins was asked if he was German or Hungarian while a gun was pointed at his chest. He replied in Hungarian and was allowed to stay. Some of my family were able to stay, some not. For example my grandparents. There were various reasons for this like supporting the Germans during the war but also if one acknowledged one's German nationality in previous censuses: “We were all German, our mother tongue was German. That was the reason for the expulsion – and that we were not communists. One should have gone to the party. That would have been the only chance to stay at home,” says Anton Baldauf in an interview for the project “Geschichtswerkstatt” ("History Workshop") in the district of Dachau about the deportations from Dunakömlőd after Germany's defeat during the war became apparent. In Dunakömlőd it was announced in writing that they would be expelled. People were mistrustful and didn't believe that they would be travelling to Germany. When they arrived in Austria, they were relieved. A contemporary witness from Ivánbattyán describes similar events: People from Dunakömlőd and Ivánbattyán were afraid of being brought to Russia. That had happened to some of the residents before.

Expulsion meant: Homeless from one day to the next

On June 7th, 1946 Ivánbattyán was occupied by the police, an American commission appointed who had to go. On June 8th, the list with the names of displaced persons was drawn up in Villány, eight kilometres away: on the list my grandpa, his brother, his mother from Beremend, his grandparents from Ivánbattyán. On June 14th, the deportation operation is called off by the police, in a false hope the listed villagers unpack their things again to be made aware in the middle of the night that they must assemble at the train station in Villány the next morning. House keys were given to the new settlers – I couldn’t find out who they were. At the train station, the luggage was checked and whatever the police liked was kept. The deportation from Ivánbattyán began on June 15th, 1946, and the train set off on the second afternoon. They arrived in my current home on June 24th. They were initially housed in an interim storage facility of the WMF branch factory, a manufacturer of household goods.

Expelled to Germany: Where am I at home now?

For a while, my grandparents could still speak Hungarian, they often drove back to their homeland, visited families who were still living there and their beloved holiday resort of Harkány, which is close to my grandparents' hometowns.

My great-grandparents didn’t teach Hungarian to post-war generations anymore. Although my grandparents were still children when they came here, nobody spoke Hungarian to us. My great-grandparents used to speak Hungarian when nobody should be able to understand them, my father remembers them sitting on a bench in front of their house. Their son, my grandfather, was too proud to continue speaking Hungarian, he said: "They didn't want us, so we don't speak the language anymore." His injured pride seems to have spoken from him here. Hurt that they were evicted from their home.

At school everything was taught in Hungarian, the mother tongue in Dunakömlőd was German. According to a contemporary witness from Ivánbattyán, attempts were made to Magyarize the population between 1920 and 1940: names were exchanged for Hungarian, and German children were not supposed to speak German on the street. German lessons were given for one hour a week and increasingly again only from 1939/1940 until the end of the war in 1945. After that, Hungarian was taught again.

Is this really our and also my identity?

It is paradoxical how conceptions of identity shifted. While some identified themselves as Germans living in Hungary, this country was still their home. After all, that's where they were born and raised. The roots were apparently seen in Germany, while after the expulsion we as a family clearly saw the roots in Hungary. And I can understand it: The families lived there for like 200 years. In our case, in summary, three verifiable generations were born and lived there in a time period of 77 years. And someone from the family even lived there before them. Connections like letters or relationships from Hungary back to Germany in the 18th century were not handed down to newer generations. For my grandparents, Hungary was definitely home – if you define the word as the place of origin. They arrived here, the centre of their lives was here, here was their (new) home.

In her book, even Nora Krug shows that she is homesick and that home means more than traditions. “We're all shaped by the time and place we grew up in”, said Nora Krug in an interview about her book with Louisiana Channel. In her book she also shows objects that embody “Heimat” for her – such as plasters from Hansaplast or curd soap. Things that illustrate home, which she can no longer have in America and which she now misses – a part of her identity that she lost when she emigrated. Unfortunately, nothing is left of our multicultural past, which was sometimes more, sometimes much less harmonious in Hungary. So maybe it is okay to feel sad sometimes that I have no connection to Hungary anymore. But otherwise – I don’t want to be there when I look at the current political situation. Would I say that Hungary is my place of belonging after all? I’ve been there once when I was really small and my grandparents wanted to show us where they came from. No, I don’t belong there. But the experiences of my family are part of my identity and my connection because this explains why I am in Germany today by explaining why they were there. I identify myself as European.

The family of my Jewish, Israeli fellow student Guy Salem also left their homeland behind – but later: They did not travel from Egypt to Israel until the 1950s. For many Jews, Israel was a safe haven after the Holocaust. For his family, however, not because of the Holocaust, because Jews were persecuted in North Africa, but the Nazis did not get as far as Egypt. Before he hadn't questioned his ties to Israel, what it looks like after his research, you can read in his article "Where did you come from and where are you going?".