“Nothing is more universal than personal things”

How can you live on with devastating memories? Some Holocaust survivors experience a significant change in the way they deal with the trauma during their lifetime. In the graphic novel "Second Generation: The things I didn't tell my father", Michel Kichka describes in a very personal way his father’s development from being unable to talk about his time in Auschwitz in his early years to working as a contemporary witness and telling his story repeatedly in his later years.

Michel Kichka shares how his father, Henri Kichka, affected his life as a second-generation to the Holocaust, moving from silence to endless talking and even a humorous approach to the family-trauma.

A similar development can be observed in Israeli society. In the newly founded state right after the war, people wanted to forget, and they kept silent. It was too hard to find words and there were too many other problems to be solved. With time however, this changed.

Private memory versus collective memory: the private story of the Holocaust survivor Henri Kichka and his family can be understood as a mirror to the story of the state of Israel and its national memory-culture, although the Kichkas did not come to Israel right after World War II.

From Belgium to Israel

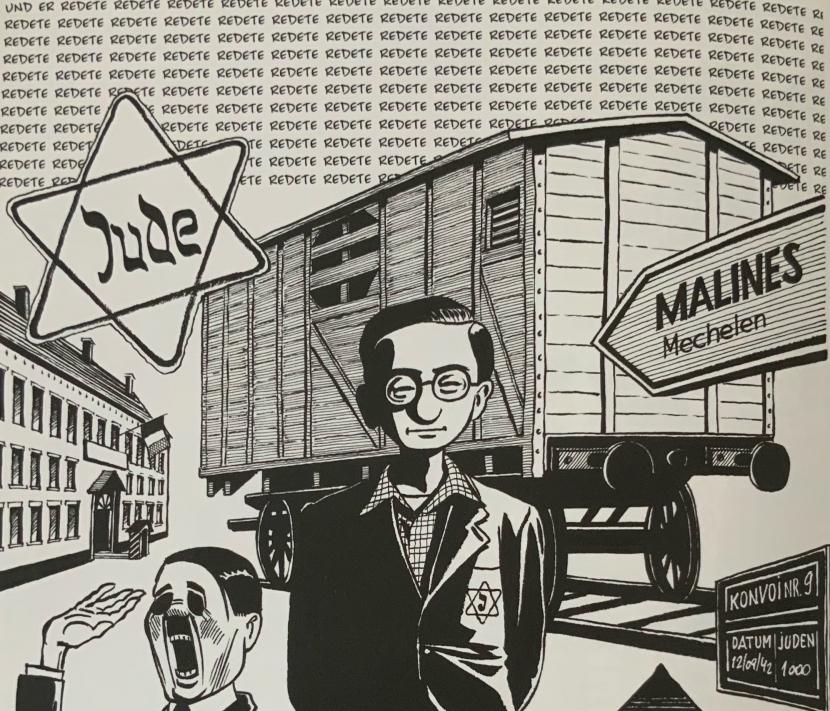

Michel Kichka was born in 1954 in Belgium. He immigrated to Israel in 1974, studied art at the Bezalel Academy, and later became a professor there. He is one of Israel’s leading comic book artists and political cartoonists. His father Henri Kichka was born in 1926 and deported to Auschwitz in 1942. He was the only one in his family who survived. He became one of the most known Holocaust-survivors as he wrote an autobiography, appeared in the press and gave his testimony to thousands of young students over the years. Henri Kichka died from COVID in 2020, at the age of 94.

When Michel Kichka decided to write a comic story about his childhood and adolescence overshadowed by the Holocaust, he was inspired by Art Spiegelman’s groundbreaking work “Maus". It took Michel Kichka a long time to both plan and complete his book, but it was an immediate success and has been translated into 17 languages.

Memory Culture

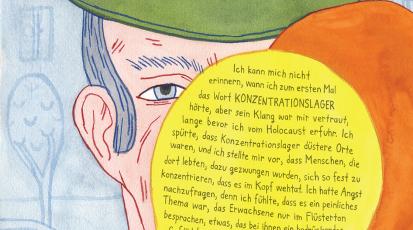

The word "Shoah" (Holocaust) expresses great destruction in the Bible in the book of Jeremiah. Over years, it has become the specific reference to the extermination of European Jewry during World War II (as opposed to "genocide" of other ethnic groups). The memory of the Holocaust in Israel has been shaped over the years by the social and cultural ethos. The transformation of this memory-culture is expressed in commemoration, public consciousness, education, and representations in popular culture. In Kichka’s graphic novel, there is another implication for the Holocaust memorial culture, and it is within the family, mostly with the children.

Silence after the Holocaust

The first two decades after World War II were a period of repression and silencing of the Holocaust memories in Israeli consciousness. They were only a marginal component in the Israeli identity. The documentation of the Holocaust and its memory were necessary for Israel's international legitimacy and Zionist ethos, but nothing more. Beyond legislation relating to them in the 1950s, like the Martyrs and Heroes Remembrance Day Law (1959), there were no other collective aspects of these memories.

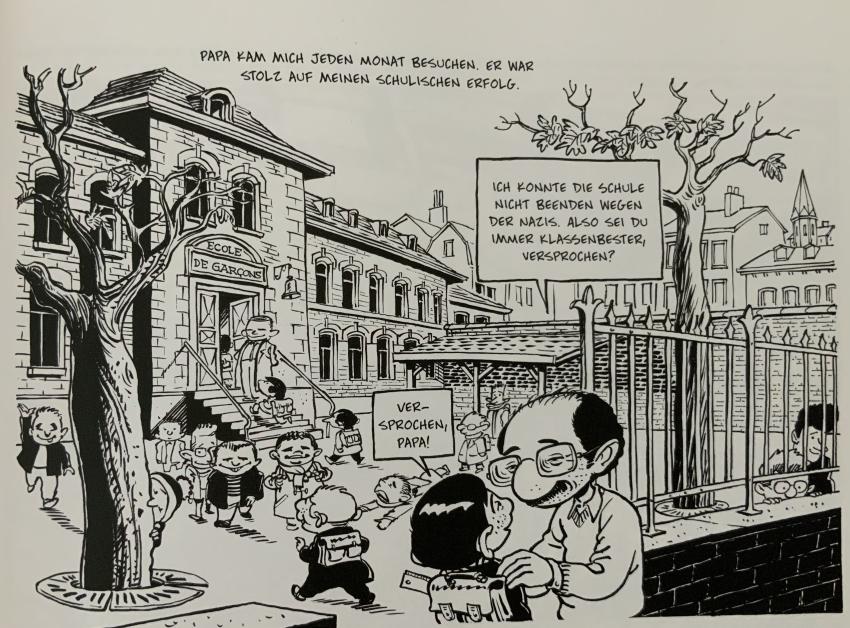

At the beginning of the story, Henri Kichka is silent about his personal story and what he has gone through. He expresses hardly anything about his past. Even his own children discover the Holocaust only through books and pictures and not directly from him. Every now and then Henri makes comments that cause confusion, especially for Michel. Henri has a great need to create the perfect family and measures his entire life by the yardstick of Auschwitz. He talks about Hitler and the Nazis and about the fact that his children now can achieve what he could not. His family is his victory.

Reappraisal of the past

In 1961, Adolf Eichmann, who had a senior position in the Nazi leadership during World War II, was prosecuted in Israel. The testimony heard in the trial revealed, for the first time, the Holocaust in its vast dimensions to the Israeli public, thus breaching the barrier of lack of knowledge. A few years later, before the 1967 War, the atmosphere in Israel was one of hopelessness. Fear of the Arab states was felt in every household. It started a new awareness of the fate of the Jewish people, exposed to the danger of extermination in their own country and not only in exile (Europe).

At the ‘Shiva’ (a Jewish act of comforting the family of the dead during seven days) of his youngest son, Charli, who took his own life, Henri starts to speak. For Michel, who had lost his youngest and closest brother, this was completely incomprehensible. He could not pay any attention to his father's story, which he had so eagerly wanted to hear all these years, because the Shiva was about Charli and not about Henri. For years, Michel struggled with forgiving his father for opening up after years of silence during the “wrong” time of the family mourning Charli’s death. However, from that day on, everything changed; and that family disaster opened the door to everything Henri had kept inside him for all those years.

Another wave of awareness appeared after the 1973 Yom Kippur war, when the weakness of the State of Israel and its soldiers became apparent. There was a new understanding of the complexity concerning the myth of "heroism." The Jews in exile who were murdered in the Holocaust or survived and came to Israel were perceived as "sheep for slaughter." Abba Kovner, one of the Jewish partisan leaders during World War II, used this phrase, which is taken from Isaiah, but in a different context during that time. After this war, heroism during the Holocaust was redefined to include not only the rebels but also the mere compliance and survival in the inhumane conditions. Surviving day-by-day, keeping the religious commandments secretly, or self-sacrifice to save another family member are all examples of heroism during the Holocaust as it is perceived and learned today.

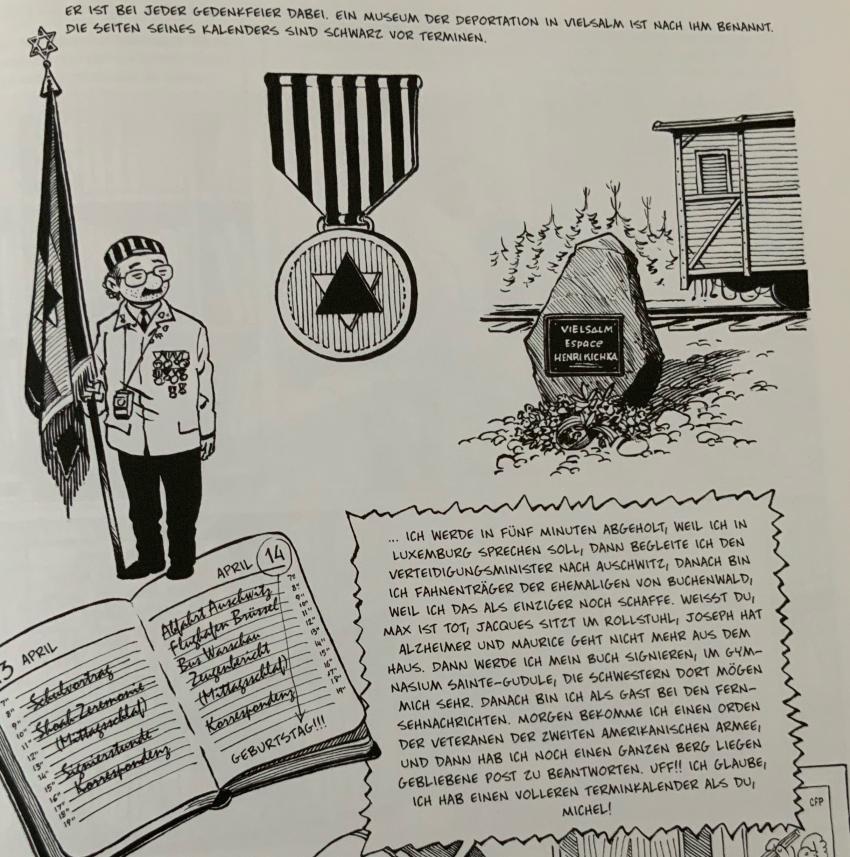

Henri becomes a busy man, speaking in front of many people in different countries to tell his own personal story. He goes to dozens of delegations to describe Auschwitz as the main testimony-giver and he writes his own book.

Sense of humor

The years after that, with the change in Holocaust education and the technological advances that enabled the filmed documentation of survivors, the memories became individual. Terms such as "the Jewish people" and "the six million" were replaced with the names and faces of survivors and victims of the Holocaust. A new understanding of the value of one personal story for preserving long-term memory had begun. Survivors shared their stories after years of trying to assimilate in “normal” society or avoiding facing their trauma. There was expansion of individual and visual databases.

In the 90’s a change began in the cultural representations – in art, literature, film and social networks. One of the main examples is the use of humor., both tragedy and comedy. Until the 90's, there was a very clear dichotomy between the tragedy of the Holocaust and comedy. Any reference that was not made with holy anxiety to the Holocaust was labeled to be political provocation or contempt and was condemned. However, both tragedy and comedy have the philosophical ability to deepen our understanding of the darkest and most inexplicable aspects of human existence.

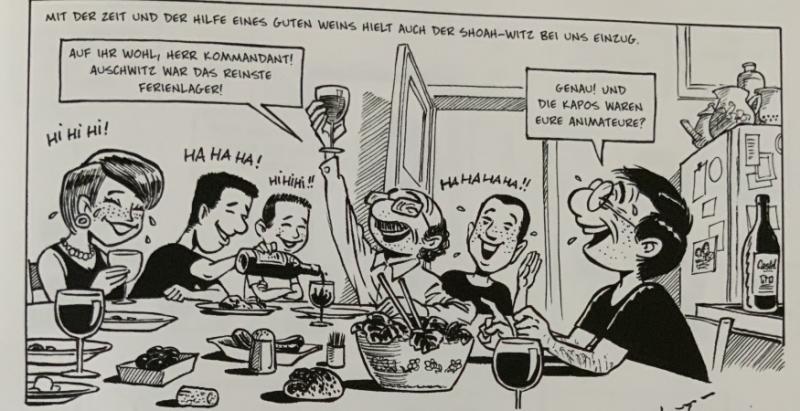

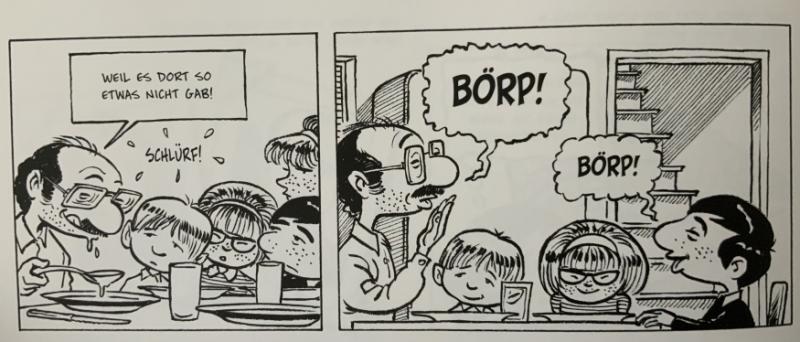

At the end of the book, the entire Kichka family, which has never really talked about the Holocaust, make jokes about it at the table. They laugh about the striped pajamas and the tattoos on his arm as if they were beautiful memories that were gladly shared. If you compare this with another scene at the beginning of the book, when the family was also sitting at the table but without shared humor about the Holocaust, the differences are striking.

Inner Peace

At the end of the story, Henri Kichka seems peaceful and satisfied. He has the feeling of contributing something to the world. You can see this in his facial expression in the graphic novel. He is cheerful in almost every drawing. It is interesting to hear how his son, Michel, perceived that transformation process, as he is the one that tells us about it in the book.

We see that the process of memory-culture transforming in Israeli history is long, gradual, and multi-layered, just like the life of a private person dealing with trauma such as the Holocaust. We compare those transformations to show that the personal complexity of those who survived is a kind of living micro-cosmos of the Holocaust memory. From silenced and suppressed memory to a shared and educated memory, from victimization to heroism, from the collective to the individual memory. All this versatility is folded into Michel Kichka’s graphic novel – perhaps his own closure to his relationship with his father, Henri Kichka.

Michel Kichka gave us deep and meaningful insights through his life-story; both in his novel and in the special interview we had with him. It is challenging for us, generations Y and Z, who have no family connection to that dark chapter in history, to understand how second-generation survivors grew up with that atmosphere in their lives. Nevertheless, we are very grateful to have been able to learn about it and discuss it, while deepening our insight into the graphic novel "Second Generation" and its sub-textuality.

For the whole interview with Michel Kichka: https://youtu.be/dYlxMZIGPP4